To understand horse color in general, you first must understand the three base colors and how they work. However, I won't touch much on the latter bit, as that is very complex and I don't want to confuse you (or myself, for that matter). So, to learn how each base color came to be, I'd suggest reading what D. P. Sponenberg's "Equine Color Genetics" has to say about it.

Anyway, to get back to the point; there are three base horse colors. There isn't any certain order, but I chose to arrange them as bay, chestnut, and black - as that is generally the order in how common each color is. Of course in some breeds, such as the Friesian and Suffolk Punch, they have been bred selectively for so long that it is rather difficult to get a chestnut Friesian, or a black Suffolk. And at least for the latter breed, if the horse is any color other than chestnut, it can't be registered anyway.

I imagine you all know what a bay, chestnut, and black horse looks like. Just in case you don't, here's a short description of each.

- Bay - A body color ranging from medium-dark brown, and oftentimes having a reddish tint to it. The points (tips of ears, mane, tail, and lower legs) are black. Sometimes a bay horse can have countershading and some people may think their horse is just a darker colored dun. Thankfully, there are more characteristics to a horse with a dun gene than just a dorsal stripe. There are also some subtypes to bay, and those are listed below.

- Sooty Bay - The sooty effect on any color simply means that the horse has a slightly darker body, with a few areas (head, flank) being the color underneath.

- Wild Bay - If you've ever seen pictures of a Przewalski's horse, then you probably have an idea what a wild bay is. A wild bay can be quite lighter than a normal bay horse, and the black on the legs doesn't always start till about the pastern, and even then it isn't always that black.

- Chestnut - This is simply a yellow-to-red-to-brown colored horse. They can have flaxen mane and tail as well, but that doesn't have anything to do with the genotype as far as we know.

- Liver chestnut - A liver chestnut may sometimes be confused for a bay, but in reality the genotype is exactly the same as a chestnut. The phenotype, however, is a lot darker. Liver chestnuts can still have flaxen mane and tail.

- Sorrel - In reality, sorrels are the same as chestnuts, but some people (and breed associations) just prefer to use different words. To get around this inconvenient issue, some horse geneticists will just use the term "red".

- Black - This is a completely black horse. When identifying a black horse though- one must be careful. Generally the easiest way to tell if a horse is really black is to search for the absence of red hairs near the eyes, flank, and pasterns. However, one also must keep in mind that some black horses will bleach out in summer (known as a summer black) while others will not (known as jet black).

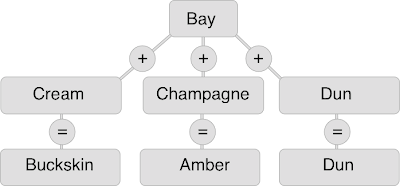

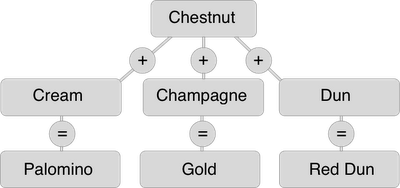

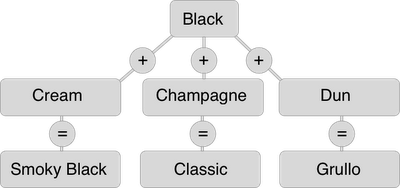

Anyway, below are some charts to help you understand three common color genes in conjunction with the three base colors. The top layer is the base color, the second is the gene, and the third is the resulting phenotype. Also, for the champagne resulting colors it is not just a single word, but the word and then "champagne". For example, a gold champagne would be called a gold champagne, but not a "gold".

P.S. - If a horse has two copies of the cream gene, the affects will be different. Two copies of the cream gene on a bay or black results in a perlino, and two copies of the cream gene on a chestnut results in the lighter colored cremello.

No comments:

Post a Comment